- Robert meets World

- Posts

- Social Truths or Forgotten Lies?

Social Truths or Forgotten Lies?

If memory serves, I came across the following statement reading @naval’s tweets:

Society is a collection of individuals who have decided to forget something in common.

At first glance, the statement is an incendiary comment about the nature of the collective, though not necessarily anti-social; there is no moralization attached unless one considers the highest principle of morality to align themselves with Truth (one could do worse than this). Yet, there is a penetrating quality even at the outset. To the admonishment of that pesky German’s voice (1), I’d like to expand upon this idea of “false truths,” “forgotten truths,” or “social lies” as I sometimes think about them, in a few examples within this note—a smarter one than I, calling them “social truths” from time to time (2).

Thanks for reading Robert’s Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The falseness of an opinion is not for us any objection to it: it is here, perhaps, that our new language sounds most strangely. The question is, how far an opinion is life-furthering, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps species-rearing, and we are fundamentally inclined to maintain that the falsest opinions (to which the synthetic judgments a priori belong), are the most indispensable to us, that without a recognition of logical fictions, without a comparison of reality with the purely IMAGINED world of the absolute and immutable, without a constant counterfeiting of the world by means of numbers, man could not live—that the renunciation of false opinions would be a renunciation of life, a negation of life. TO RECOGNISE UNTRUTH AS A CONDITION OF LIFE; that is certainly to impugn the traditional ideas of value in a dangerous manner, and a philosophy which ventures to do so, has thereby alone placed itself beyond good and evil.Beyond Good and Evil, Prejudices of Philosophers #4, F. Nietzsche (1886)

If you have been on this planet long enough, I hope you have, you are presumably fascinated and frustrated by the paradoxes present therein—comical wisdom of nature to provide us with embedded entertainment. The absurd nature of reality is often central to Oriental instruction, particularly in metaphysics and spirituality. That, for example, a false statement can be true seems, to those of us not blessed in natural instinct toward formal logic, a contradiction. If the reader does not object but for a singular example dripping with irony:

“Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.”Tao Te Ching, Master Lao Tzu

The concept of “social lies,” in a specific case, is described by the philosopher Rene Girard in Mimetic Theory—a description of the origin of religion and culture. Girard argues in his landmark title Things Hidden Since the Foundations of the World that the locus of culture and society began with a secret, a forgotten truth: a founding murder (3). Girard’s analysis of primitive and contemporary myth, up to and including Christianity, yields the theory that, in part, the purpose of myth, the sacred, and its persistence through culture, has been to carry the species-preserving quality of the scapegoat mechanism. The scapegoat mechanism, to recklessly simplify more than is prudent to do so, is a process in which the collective, at a moment of crisis, selects an individual possessing the dual status of “insider” and “outsider” to persecute and blame for the collective’s pain, anxiety, and ailments. Such persecution often ends in a murder which, according to Girard, offers a temporary panacea to the crisis, only to repeat at a future junction. The mechanism serves to combat what Girard (and others (4)) consider an implicit and inescapable property of human social systems: envy, mimesis, and mimetic desire.

An intriguing consideration of Girard’s theory is the central observation that social lies are hidden in plain sight. Girard offers an interpretation of myth that highlights the essential effacement of its origin (i.e., collective persecution and murder), opting to recast instead into “voluntary sacrifice” that is characteristic of mythopoetic tales. In doing so, Girard argues, the adaptive process which has served to keep the collective united persists through time (5). Girard further elaborates upon the adaptive mechanism solidifying itself into collective consciousness through the unifying idea of “the sacred.”

Ignoring its irony, we can demarcate the profit obtained from “social lies”; the rhetoric offered in the anthropological title Sapiens by Yuval Harari provides two such examples. Harari points out that social ideas such as corporations and nation-states are, in fact, agreed-upon fictions. Both ideas, from the perspective of social utility (measured as survival and reproduction of the collective), are beneficial (8). The truth of the circumstance is revealed in the very technical language present in the legal framework:

A corporation is an entity that acts as a single, fictional person. Much like an actual person, a corporation may sue, be sued, lend, and borrow.

Nietzsche describes in the quotation for Beyond Good and Evil above,

“The question is, how far an opinion is life-furthering, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps species-rearing, and we are fundamentally inclined to maintain that the falsest opinions.”

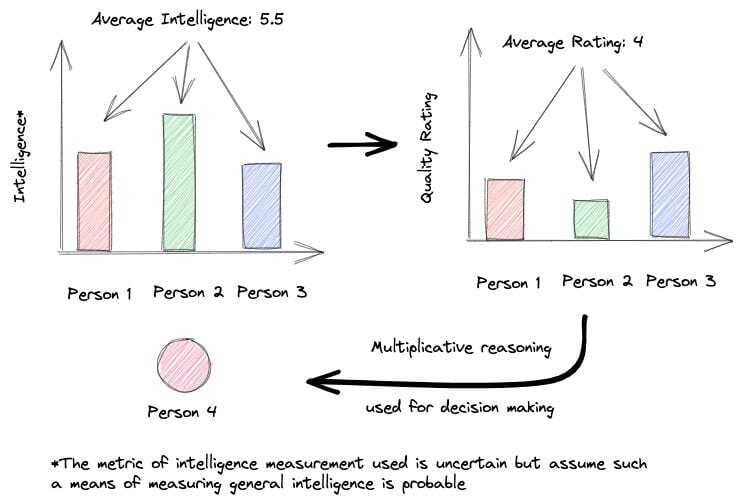

That is, though intelligibly false, a certain opinion or concept can be useful in its capacity to further the species. Social proof is a heuristic used to evaluate and filter prospective challenges, serving to conserve mental bandwidth. The internal logic observes that by the multiplicative effect of others’ reasoning and positive conclusions, it is probable that the decision made is of good quality; the so-called, “wisdom of the crowds.”

Figure 1: The internal calculus of the individual considers that distribution of intelligence creates a mean intelligence value which acts as a stand-in for “thinking horsepower”; this metric is assumed in application to the sample’s rating/conclusion on a given decision (e.g., buying a product, using a business, etc.).

What is central to this observation is that if one is seeking average outcomes, the use of social consensus tools is valuable when time (or desired effort) is scarce. A corollary is that in pursuit of non-mean outcomes, consensus may provide the very antonym to the desired result.

“Wide diversification is only required when investors do not understand what they are doing.”W. Buffett

Where wisdom can become folly is with the collective choosing, under some pressure or crisis, to unilaterally concede on a given position. More too, is the matter of determinate layers in which the consensus has been made—a question of depth and abstraction.

Footnotes

“It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what others say in a whole book.” — F. Nietzsche

See The Peter Thiel Question Footnotes #4

It is a fascination to me, in its own right, that the first Biblical story following the creation of the earth and Fall of man, is the same story of a murder: Cain and Abel.

See Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan

If Girard’s perspective about Scapegoating is accurate, from the evolutionary psychology lens (a lens met with, rightly, heavy skepticism from critics), one might argue that the given process of “scapegoating” has a selective advantage.

This is under the contextual perspective of anthropocentrism.