- Robert meets World

- Posts

- It is Not Suffering We Fear, but Meaningless Suffering

It is Not Suffering We Fear, but Meaningless Suffering

Why the meaning behind the struggle can matter more than the destination

In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche offered an insight into the human condition that contradicts our modern obsession with safety:

"Man, the bravest animal and most prone to suffer, does not deny suffering as such. He wills it. He even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering. The meaninglessness of suffering, not suffering, is the curse that lay over mankind so far." — F. Nietzsche, On The Genealogy of Morals (Part III, Section 28)

This is a powerful idea because it highlights a biological truth:

Evolutionarily, we are built for survival and adaptation, not comfort.

Our psychological hardware is wired to embrace challenge. '

Historically, this was out of necessity, today, ascending the levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy, we face the necessity of voluntary engagement with struggle.

Life-Affirmation vs. Life-Denial

But Nietzsche's insight carries a discernment often missed: the difference between a life-denying meaning and a life-affirming 'why.'

Nietzsche criticized the "Ascetic Ideal"—the historical tendency to give meaning to suffering by denying life itself (suffering now for a reward in the afterlife).

A life-affirming 'why' does the opposite.

It harnesses voluntary suffering—discipline, challenge, focus—not for denial, but to intensify life in the present.

It drives you toward the realization of potential.

This isn't just philosophy; it is rooted in our physiology.

Neurophysiology and the Will to Become

The act of forward-looking, goal-directed discipline is wired into our concept of time and self-becoming.

The 'why' acts as a high-value future reward signal.

The brain is essentially a prediction machine.

It tolerates the discomfort of present discipline because its reward circuits (specifically the dopaminergic pathways) anticipate the vastly greater reward attached to the completion of the task.

Crucially, our ability to vividly construct and commit to a "better version" of ourselves engages the Default Mode Network (DMN), a set of brain regions critical for autobiographical planning.

This capacity to delay gratification and willingly endure present discomfort for a projected future gain is the engine of human becoming.

It is the constant process of self-creation that defines us. [2]

The Changing Form of Challenge

The choice to voluntarily engage with struggle is a modern problem though, vividly outlined in works like The Comfort Crisis.

In prior eras of strict survival, our 'why' was innate, concrete, and non-negotiable.

Why am I struggling?

To eat. To survive the winter. To secure the tribe.

The suffering was involuntary, and the meaning was immediate.

However, once basic needs are met (often through abstract systems of economics rather than physical exertion), the immediate, survival-based 'why' is more difficult to feel.

This leaves a vacuum.

The challenge is no longer fighting starvation; it is fighting meaninglessness and the corrosive effect of endless comfort.

If the physical world no longer forces a visceral 'why' upon you, you gain the profound, difficult responsibility of engineering a meaningful challenge.

This capacity to choose the form of your suffering is a prerequisite to avoiding psychological wasting.

The Psychology of Optimal Challenge

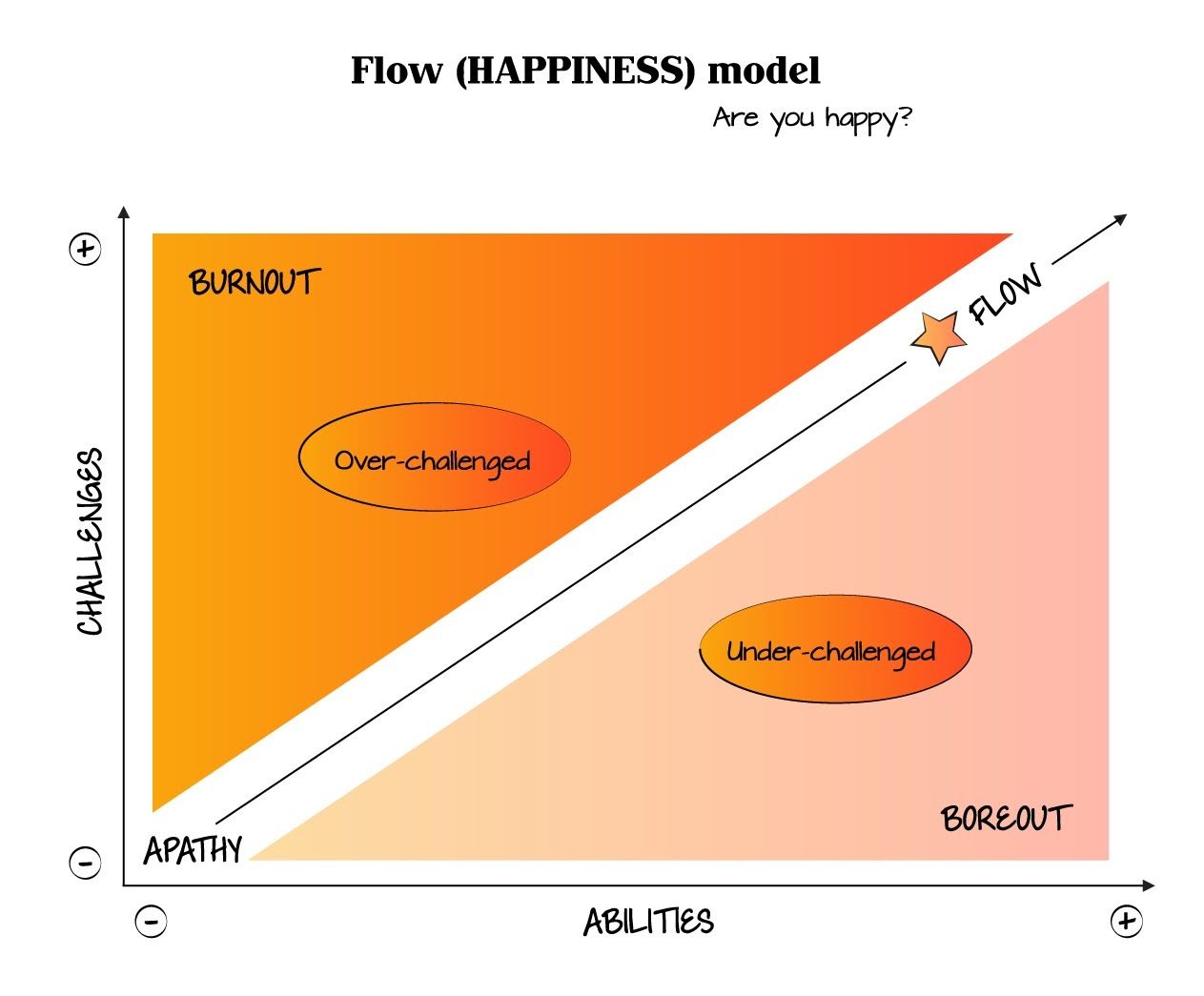

This philosophical need for struggle finds a modern echo in the psychology of optimal experience.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of Flow—the optimal state of performance and immersion—requires an adequate challenge met with adequate skill. We don't struggle because a job is difficult.

We struggle when we lack a greater vision tying us to the necessity of that discipline.

As detailed in Daniel Pink’s Drive, humans deprived of a flow state suffer rapid psychological deterioration.

Without a challenge to met, anxiety and entropy set in.

We are driven by the need to contribute to a greater whole, but this creates a paradox of scale.

Finding a 'Why' Beyond the Abstract

"Contribution" is a deeply abstract concept.

Our brains are wired for tribal units of about 150 people (the Dunbar number).

We cannot easily grasp the idea of serving "humanity" (8 billion+ people).

Therefore, relying on a generic desire to "help the world" often fails to motivate us through hard times.

Our brain needs a concrete, visceral definition of meaning—a personal "why"—to willingly exit the safety of the container and, to use Joseph Campbell's analogy, follow the call to adventure.

The Weight of a Personal 'Why'

I experienced this friction deeply in my own career.

Originally, I intended to become a physician.

But throughout my four-year degree, I faced a recurring crisis: What will I do with a biochemistry degree if I don't go to med school?

In the quiet moments, however, I realized Med school didn't align with my internal compass.

My drive toward it was fueled by a scarcity mindset—a fear of the unknown—whereas the world of Information Technology offered a frontier of expansion.

Ultimately, I made the difficult decision to pivot from Medicine to Software.

The transition involved studying two degrees simultaneously.

It was no walk in the park; I wanted to quit often.

But the suffering was voluntary and sustained by a potent "why":

The opportunity for self-expansion—seeing the best version of myself realized through entrepreneurship and technology.

That "why" powered me through the difficulty.

It was curiosity about computers that drove me to read textbooks and seek out programming opportunities when I was just a digital marketing intern.

The nature of the "why" is deeply subjective.

It is a felt sense.

It is followed by a curiosity, a pull and an sense of impending commitment fuelling you through the discipline ahead.

A Function of Grace and Time

Understanding the nature of the 'why' is more important than having a prescribed method for finding it.

It is also important to realize your ‘why’ will evolve over your life; it is not a static target to worship forever.

In prior cultures, young men underwent formal initiation rites—such as the Lebollo in Southern Africa, the Bull Jumping of the Hamar, or the Vision Quest among Native Americans. They were separated from childhood and subjected to structured suffering to acquire the courage required to find their place in the tribe.

Today, we have no such rituals. Finding your next deep 'why' is not a formulaic process; it is a function of grace, time, and experimentation.

Focus on creating space to listen to what genuinely aligns with your inner sense of commitment, rather than forcing a logical conclusion [3]

Follow the curiosity that feels like a truth.

This inner sense, more than any abstract goal, will provide the fuel for the disciplines and challenges that lie ahead.

Footnotes

[1] A Necessary Caution: This is not without its dangers. See Who Are You When You Stop Becoming? regarding the risks of over-identifying with future goals.

[2] The Risk of Postponement: If the 'why' only exists in the distant future, the disciplined present becomes a miserable means to an idealized end. This state of perpetually living for "what will be" can prevent presence and lead to anxiety (a caution echoed by thinkers like J. Krishnamurti)

[3] Something the author is admittedly challenged at