- Robert meets World

- Posts

- Cold. Hungry. Wet.

Cold. Hungry. Wet.

I watched in anticipation as the mass of participants trudged their heavy boots and uniforms through the sinking sand of San Diego Mission Beach. Focused in coordinated effort, they moved heavy wooden logs from one end to the next. It must have been around 3 or 4 AM with darkness shrouding a dimly lit shore and tides lapping in the background.

The camera cut to a close-up of the facilitator’s face as he quipped to the group in an authoritative, sadistic announcement:

Time to go get wet again!

The candidates in Phase 1 of the BUD/S Navy Seal qualification program looked at one another in a state of misery: a wave of consideration to throw in the towel in their gaze. The thought of another humiliating bath in the frigid Pacific followed by rolling in the sand for several minutes after seven grueling weeks of physical, mental, and emotional adversity weighed on their shoulders; the moment lasted only a still frame, as the candidates resolved to haul their panting, cold, and ragged bodies into the ocean once more.

Two months after seeing the events in the BUD/S documentary unfold, I dragged my tired body outside into the cool San Francisco night. Not quite close to the conditions experienced by BUD/S participants (an apartment pool doesn’t instill the same rawness as a 3 AM sandy beach), I sat above the water for my second week of Stewarts Smith’s self-directed 12 Weeks to BUD/S (1) general physical preparation course. I had no intention of applying to the BUD/S program but was curious about the fitness levels and challenge to “train like a Navy Seal.” As I descended into the cold pool, three words bubbled into my head:

“Cold. Hungry. Wet.”

I have a difficult time avoiding Darwin in the hallways of my mind. His evolutionary model seems to jump out from every janitorial closet and at inopportune moments to influence my understanding of the world. Human physiology, from the mind to basic metabolism, is a product of millions of years of adaptation—challenge and response to the environment. Curiously, however, natural selection isn’t an optimizer but a satisficer (2)—preferring what is “sufficiently better” rather than optimal. This history leaves us with a breadcrumb trail of curiosities, like an elderly man investigating a youth-filled time capsule. The appendix is one example, often considered useless, though it may serve as a reservoir for beneficial gut bacteria.

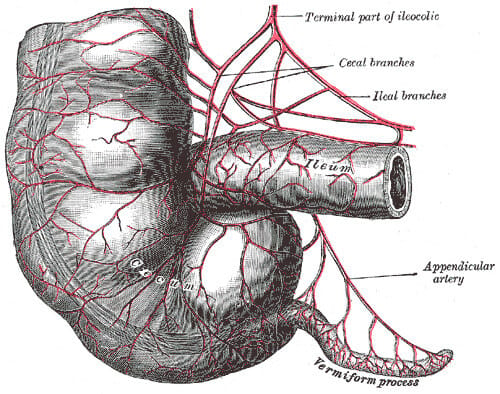

Figure 1: An anatomical image of the arteries of the cecum and appendix (labeled as Vermiform process) via Wikipedia

I struggle between heroic enlightenment rationality and the skepticism of empiricism. Western culture, especially the economic system, seems particularly obsessed with rationalism—often to nauseating levels. For example, public market investors pursue companies to “trim the fat,” leading businesses to amputate parts for efficiency. Sometimes the patient lives; in other cases, it endangers itself, as seen in Long Term Capital Management, detailed in Roger Lowenstein’s When Genius Failed. The PhD-run hedge fund aimed to squeeze inefficiency out of the market, profiting short-term but risking long-term disaster.

The words “Cold. Hungry. Wet” capture three environmental challenges our ancestors might have evolved under for millennia, which the body operates well within. These words explain the rising adoption of “new” rituals claiming enhanced performance and well-being. Alternating abundance and scarcity of food is simulated through intermittent and extended fasts; ‘Wetness’ through brief periods of intense exercise or sauna use; ‘Cold’ through cold plunges and showers. All of these, perhaps, mimic conditions our ancestors experienced, responding to today’s environmental challenges like calorie abundance and comfort.

I’m left to wonder: in search of wellness, what old practices will soon be new once more, and what part of culture (5) remains ‘un-mined’ for its nourishing benefits?

Footnotes

(1) See Stewart Smith’s 12 Weeks to BUD/S blog(2) See Satisficing on Wikipedia(3) We ought to humble ourselves; time will make a fool of us. Optionality is an advantage (4), and we don’t know when, what, or where nature will use some obscure trait.(4) See Antifragile on Wikipedia(5) i.e., persisted collective experience